Nutrition

Carbohydrate Loading: When, how and why?

Carbohydrates are the body’s main source of energy. ‘Pasta parties’ have become a common part of the lead-up to long-distance endurance events. However, should we be ‘carb loading’ or is it less beneficial than we might think ?

1 min read

Carbohydrate loading to increase your endurance and speed is one of those topics you often hear discussed in the run-up to a big event like a marathon. Unfortunately, despite all the chat and unsolicited friendly trackside advice, it’s very rarely executed effectively.

As an endurance athlete, you know that performance depends on both training and proper nutrition. One of the most important nutrition strategies for endurance sports is carb loading, which can boost glycogen stores and improve performance.

However, carb loading can be a tricky process that requires careful planning and execution. In this article, we’ll delve into the science behind carb loading, explore different techniques, and provide tips to avoid common mistakes. By the end of this article, you’ll be ready to incorporate carb loading into your training plan and achieve your best performance yet.

WHAT IS CARBOHYDRATE LOADING?

Carbohydrate loading is a strategy used by athletes to maximise glycogen stores in muscles before endurance events. Card loading can help to enhance endurance, delay fatigue, and improve performance.

It involves increasing your carbohydrate intake in the lead-up to an endurance event, such as a marathon.

“From marathoners to endurance cyclists, and triathletes to ultra runners, carb-loading is all part of the successful athletes' final week: Increasing carbohydrates in the daily diet with a view to increasing the carbohydrate in muscles, called glycogen.

This is a sign of a “serious” and organised competitor who knows carbs in the muscles allow you to go faster and longer. Behind the buzz phrase that many talk about, few actually know how to get this delicate process correct and instead perpetuate a mix of bad science and old-school processes to end up with a haphazard occasional gain.

More often though, it makes for problems not performance.” - Joe Beer

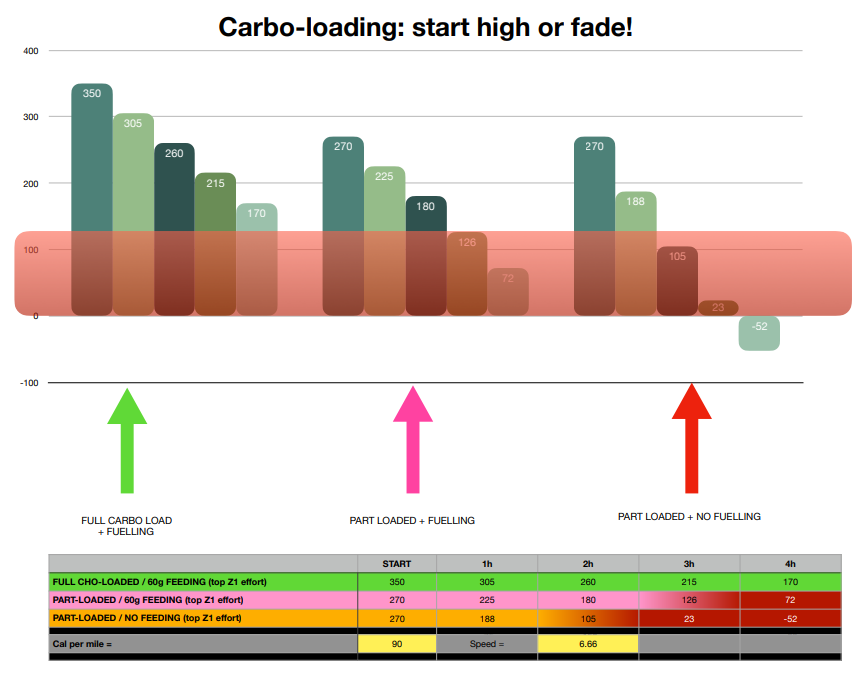

Despite what you may hear from your Bro-Science buddies, if you want to go fast (I mean properly fast) you need carbs. The human body can go slow and long predominantly using fat (and we’ve all got enough of that to use as fuel!) but to move fast or even complete at a modest pace, you need to burn glucose. The body’s way of storing glucose is in the form of a complex chain of glucose molecules called glycogen in your muscle.

Glycogen is one part carbohydrate and approximately 3 parts water, and like filling up a car, you can expect to therefore be heavier when properly carbo-loaded, in fact seeing the scales increase and veins or muscle definition disappear is a good sign carb-loading has occurred.

The content of fully loaded glycogen stores in your muscles varies between athletes between around 350 and 500 grams - the bigger and more muscular the person the more capacity to store glycogen.

Yet, the fact that exercise, training and competition are never exclusively “fat burning” means you are always nipping away at glycogen, and therefore loading is not as easy as it sounds: you have to eat enough carbohydrates in your diet, drink enough water and be resting enough to let the fuel hang around for your big day ahead.

Pros and Cons of Carb Loading

The main benefit of carbohydrate-loading is that it allows you to go faster for longer in events that are roughly 90 minutes or longer[1].

In short events, like your 5k park run, a 10-mile cycling time trial or a very quick triathlete over the sprint distance (750m, 2k, 5k) carb loading is not required.

However, as it's based on time, not distance, this means someone running a 2 hour half marathon should properly carb load, but someone doing it in under 90 minutes might not need to.

Whilst on the “cons” let's be clear about why glycogen is useful: the faster you push your muscles, the greater the proportion of fuel that comes from carbohydrates. Move at a snail's pace and carb use is very low.

Go as fast as you can for 2 hours and carbs could be used at 2-3grams a minute. “Carbs really are king” when you want to go quite far and quite fast.

The one “con” that many have found out is that eating to stack those carbs into your muscles can result in stomach issues when you compete the next day.

A loaded digestive system, inconvenient toilet stops and feeling “heavy” all play on the mind and the stopwatch to mean it could, quite literally, backfire.

When to carb-load

Not every endurance event is positively affected by carbo-loading.

If you are doing an event of a controlled pace, or even with sprints inserted like a cycling road race, 80-90 minutes or less means you do not need to fully carbo-load.

The couch-to-5k person or the team member in a corporate relay over a standard distance triathlon - well, you need not go overboard with your love of carbs leading up to events.

However, I have found that athletes who do repeated training, often with days of 2-4 hours back to back, even with various sports to spread the muscles that are included, they still need to occasionally do a carbo-load to ensure they can complete their week without quality sessions dropping off and fatigue affecting all areas of their life.

The typical person to gain from a carbo-loading is the marathon entrant, the sportive rider doing their 100k (or 100 miler) and those competing in the popular triathlon distance - the middle distance or half Ironman (aka 70.3).

Please note, the standard or Olympic distance still requires most to be loaded up as you have 2-3 hours to get to the finish banner.

The other part of the “when” it's good to do this “loading” is answered simply: not the day before. I still laugh at the response from people who carbo-load with “I’ll have some pasta the night before”. Oh dear, oh dear.

The science of loading[2] and the experience of athletes with stomach issues suggests doing it the day before the day before, simple. So a Sunday event means a Friday carbo-load.

When not to carb-load

As above, don’t carbo-load if you are pushing it for less than 90-minutes or so.

A 10k run, even if it takes you an hour, is not about overconsuming carbs for days on end. It's not a last-minute answer to not having enough fitness for a 5k or enough cycling to complete 25 miles of riding.

Carb-loading became popular around the marathon boom of the ’70s and ’80s because sports scientists had already shown in the ’60s that loading of the muscle can help the athlete go for longer at faster speeds.

Even in today's elite super fast marathons (~2h-2h20) they preceded races by carbo-loading plus further carbohydrate fuelling at most of the 5km aid stations along the route.

How to successfully carb-load

Taking all the above into account and using the science of a much-missed piece of Aussie research from the early noughties[2], you get this simple but very effective one-day load-up. No need to deplete yourself for days, or over-eat fat[3] or load for more than 1 day of carb-binging[2].

-

Weight and date

Weigh yourself to get an idea of your mass (in kilograms). Know the day and date of your race as you have to load up 2 days out from the event, e.g. if it is April 21st, you must load April 19th.

-

Times 10. Or 8.

You need to consume 10 grams of carbs per kilogram of your body weight in one day. Yes, re-read that and do not scrimp on the calculation. So a 54 kg female needs 540g and a 74kg male athlete needs 740g of carbs. Some athletes prefer to test with 8g/kg carb-load during a normal training block to see how it goes.

-

Split over the day

You need to consume the carbs throughout the entire day. For most athletes, this means 5 to 6 meals across the day focussing on carbs, e.g. 7am, 11am, 1pm, 3pm, 6pm, 9pm. In a 540g example thats roughly 90g of carbohydrates per meal. You are doing this kind of day rarely so don’t worry about macronutrient intake, quality fats and so on. This day, Carbs-Are-King.

-

Go for high-glycemic

Ignore the “go for quality carbs” as I heard a well-known running magazine put out in a recent video. Relying solely on the wholegrain or healthy carbs is just too bulky to get the 10, or even 12-grams per kilogram that has been suggested for an optimum carbo-load(1). Granola with extra honey, rice cakes with jam, snacks or confectionary (aka Jelly Babies) and carbohydrate-loading drinks - dive in.

-

Add water. Galore.

Remember that 1 gram of carbohydrate has 3 grams of water attached. Some foods do have significant water contained in them (e.g. bananas, grapes, jams) but you still need to drink somewhere in the 1L to 2L range on your carbo-loading day. Some would add a “salt-loading” regime but that's for another blog.

Best carb-loading foods

You can pretty much eat whatever you want on your carb loading day. Don’t worry about processed foods. This is a one-day process.

As eating 5-6 carb-heavy meals in a day really tests your appetite, it’s important that what you are eating is tasty and easy to get down so you can meet the required carb intake.

Ensure you complete the whole process, as many of my clients report that the 6pm and 8-9pm mini-meals are a real challenge to eat.

The worst carbo-load is trying to stick to super healthy and super fibrous foods.

This is not a social media exercise to show what super-healthy foods you eat.

The research used plenty of simple carbohydrate foods and actually supplemented the athletes with glucose powder.

Carbo-loading is the icing on your taper-cake. Enjoy your training up to events, be challenging with your goals and know that we all learn lessons along the way to the finish line.

Look after your health by getting back on a good quality diet after your event is done.

Happy racing!

Blood test for

Runners

Male & Female Tests

sports doctor review

Results in 2 working days

Flexible subscription

-

Bussau, V.A. et al (2002) Carbohydrate loading in human muscle: an improved 1 day protocol. Eur. J Apple Physiol. 87: 290-295.

-

Burke, L. et al (2018) Contribution of evening macronutrient intake to total caloric intake and body mass index. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28 (5), 451-463.

Get 10% off your first order

Want regular tips on how to make the most of your results? Join our newsletter and we'll give you 10% off your order!